Proximity and Separation #

~5 min read

The human brain is a pattern-matching machine. It is wired to assume that things placed close together belong together.

This is the principle of proximity, and it’s one of your most powerful design tools.

As a designer, you use this principle to guide your viewer. Proximity (grouping related items) and separation (using white space to distinguish unrelated items) aren’t passive choices; they are active instructions. You are telling the reader what to compare and what to consider distinct.

In design, space is never empty. It is an active tool for communication. Proximity and separation describe two extremes of spatial arrangement that can be used to help the reader understand what objects you wish them to view as similar, versus which objects you want them to consider to be different. Similar to how the use of contrast requires consistency, it is best to try to maintain a consistent proximity between objects, and then use noticeable changes in separation to signify similarity/dissimilarity between objects.

Consider the series of objects shown below. If proximity and separation are not used, then it is hard to perceive any pattern in the objects.

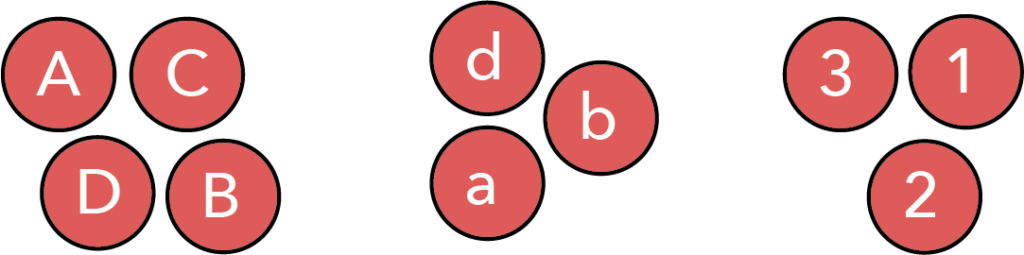

However, simply bringing these objects together, we can highlight the fact that the collection contains upper case letters, lower case letters, and numbers.

It is important to note that between these two images the relative ordering and arrangement of the objects did not change. All that has changed is to move objects we wish to be seen as connected close to one another, and create separation between those we wish to be seen as different.

This past point is a critical one: we have used proximity and separation to impose an idea of how to group objects on the viewer. The viewer will reach the conclusion that there are upper case, lower case, and numbers.

However, this is not the only possible grouping for these objects. Indeed, we can use proximity and separation to guide the reader to a different interpretation… perhaps that there are the first, second, third, and forth items of each series.

Thus, proximity and separation are powerful tools for helping the viewer see the patterns we (the designer) wish them to see, and for reaching the conclusions that we hope they will.

The use of proximity and separation in data visualizations #

Above, we have seen that proximity and separation serves two purposes. First, it functions to make the parsing of information easy for the viewer. Second, it allows the designer to bias interpretation of the image in the way that they wish. However, despite the importance and power of these two aspects, proximity and separation it is a commonly violated principle in data visualizations.

Legends are a violation of proximity #

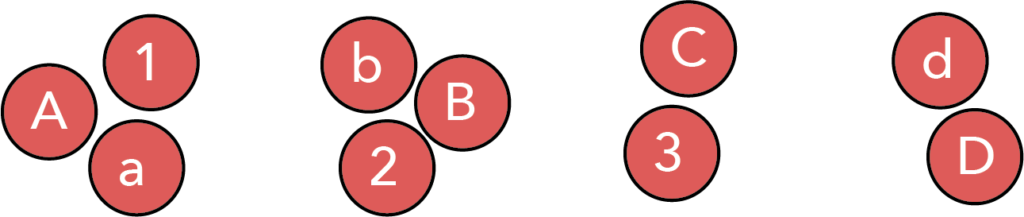

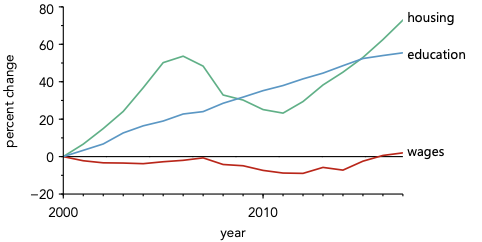

Given the ubiquity of legends, this heading may be hard to believe, but consider the use of a legend in the plot below:

Take a moment and think about what you find to be the most interesting aspect of this plot.

For me, I think the most interesting aspect is that both housing and income costs have increased over the last 20 years, but income has been relatively flat. In other words, the most important aspect of the plot is the overall tends and relationship between the lines.

Now, consider what using a legend does. Before the viewer can focus on these interesting trends and relationships, they must first focus on the legend—looking repeatedly back and forth between data and legend in order to assign each data line appropriately. Only once this assignment is made can they focus on understanding the trends and relationships shown in the plot. In other words, a substantial amount of the viewer’s cognitive load is spent just decoding the plot, not understanding its message.

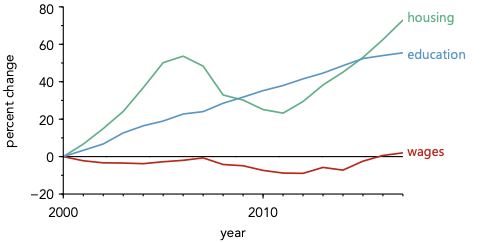

Now, consider the alternative: directly labeling data as shown below.

When data is directly labeled, instead of using a legend, assignment of data is quicker and easier. This means that the viewer is able to spend a larger fraction of their time considering the data—rather than simply trying to assign it.

This effect of using a legend is general. Thus, one should always strive for direct labeling of data whenever one can, accepting the use of a legend as only a compromise for figures where directly labeling is simply not possible.

Beyond spatial proximity #

Above, we considered spatial proximity. This is the most obvious type of proximity. However, there are also other kinds. As we will explore more in the chapter on color, some colors feel closer together, in terms of hue, saturation, or value. Thus, we can also use proximity in color space in order to make the reader see things as related.

Consider the plot with direct labeling. The direct labeling helps us assign the lines—that is true. However, the association between the labels and the data can be made instantaneous by changing the colors of the labels to match those of the lines, as shown below.

This small change creates a second layer of connection. The label and the line are now linked by spatial proximity (they are close) and conceptual proximity (they are the same color). The link requires zero conscious effort from the viewer to make.

Of course, one might also consider this to be an implementation of consistency as well. If that view makes the most sense to you, then I won’t quibble—as long as you make things that belong together as close together and as similar as possible, then you are doing the right thing!

Though I have only illustrated the use of this idea for color, I should also mention that it applies to other aspects of design, such as choices in fonts, choice of alignment, and so on.

Concluding thoughts #

Your primary goal is to make your message as clear as possible, as quickly as possible. The easiest way to do this is to reduce the work your viewer has to do.

Use proximity to group related items. Use separation (white space) to distinguish unrelated items. And use other principles, like color and , to reinforce those groupings.

When you do this, you’re building a visual argument that is clean, confident, and easy to understand.